The Developing World Needs More Equitable International Financial Frameworks

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought strenuous financial stress to governments all over the world. A specter is haunting developing countries: how are we going to finance the needed massive stimulus packages during and after the pandemic? As a consequence, ideas about tax system reform and sovereign debt restructuring are gaining terrain in the public agenda. These two phenomena show an inherent fragility in financial systems of the developing world and invite us to rethink the global frameworks of international finance.

Proposals for more progressive tax reforms are being considered in the U.S., Europe, and Latin America. Most fiscal systems across the world are somewhat but not completely progressive. A progressive tax system is designed to tax the rich more than the poor or middle class, following predetermined income brackets. This abides with a principle of economic redistribution. On the other hand, a regressive tax system is exactly the opposite: the tax burden is not distributed according to income and, therefore, the rich end up paying relatively lower taxes than most of poor and middle-class citizens. According to Landais, Saez, and Zucman, the case of the post-WWII German recovery counts as an example of how a wealth tax can help an economy recover. The need for raising or creating a wealth tax is manifesting in different Latin American countries like Peru and Argentina.

Nevertheless, taxing corporations and the rich brings up another problem: in a world with increasing free capital mobility, evading this type of tax becomes easier. Corporations might simply choose to move their money to different countries depending on how much are they going to be taxed.

This has led Ricardo Haussman to propose a global income tax. As Haussman says, given the problems with taxing capital income, many countries choose to tax labor—an incentive for the expansion of the informal economy (comprising more than half or workers in Latin America and nine out of 10 in India). Taxing global capital income is a necessary step to improving general tax systems in the developing world. Since the challenge of capital outflows associated with progressive tax systems is the worst in the developing world, international cooperation for developing a global income tax structure would especially benefit developing countries. A first step for this international cooperation would be having a better system of information that allows the national authorities to tax capital outflows and/or inflows, which is already happening in the U.S. and OECD countries. As the author says, this does not require a global government to enforce the tax, but more cooperation for each country to set an efficient capital income tax.

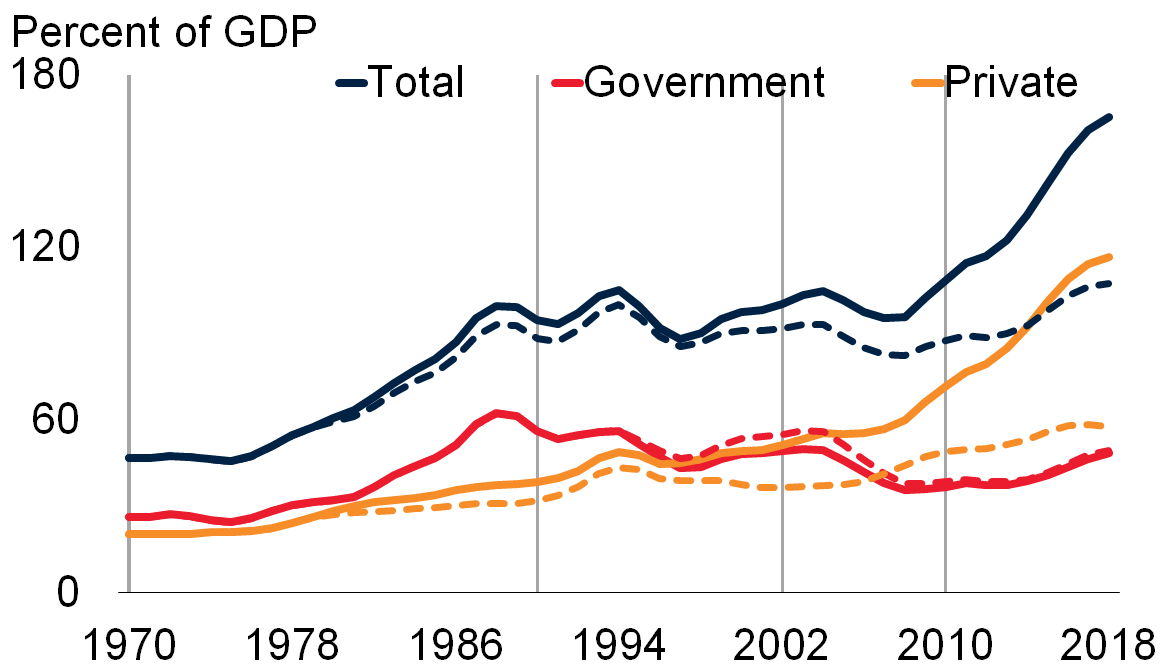

It is common to find weak and regressive tax systems in the developing world. This is an even worse problem when we look at the financial situation of emerging economies. In Global Waves of Debt, Kose et al., 2020 show how the past decade has seen the largest debt increase in the developing world:

Source: Global Waves of Debt

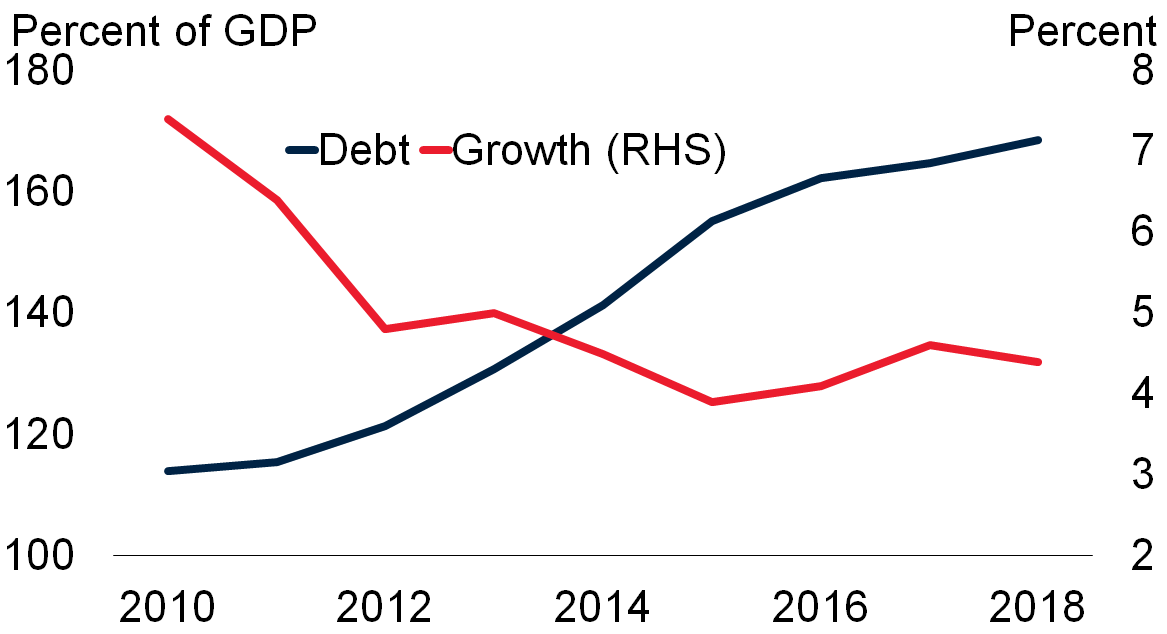

Even when debt crises might not be imminent, the situation for developing economies is still problematic, especially when we see how growth has been stagnating while debt has risen:

Source: Global Waves of Debt

The average debt ratios of 2021 are projected to rise worldwide. During the pandemic, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the G-20 have already taken significant financial support actions, such as the Debt Service Suspension Initiative. In addition to these short-term actions, there is growing consensus in the IMF about the need for structural reform of the international debt framework. But the real problem is the large number of developing countries that were already at the verge of debt crises before the pandemic. As the recovery starts, many of them are close to defaulting and/or suffering capital outflows and fiscal distress. IMF leadership has expressed concern about the need to reform the international debt architecture in three areas: collective action clauses in debt contracts, debt transparency (what do countries owe and in what terms), and a common approach for all bilateral debt restructuration processes. A key question remains unanswered: will these changes also imply a shift from the austerity model? That might be one of the most pressing problems developing countries will face when implementing post-COVID-19 debt programs.

The case of Argentina’s restructuring processes in the past few decades demonstrates the need for more equitable international financial frameworks. In 2010 Argentina went through a series of negotiations with their creditors until 93% of them accepted the terms. The remaining 7% of bondholders were vulture funds who took the case to court, bringing severe negative consequences to the country’s financial situation.

As a consequence of this and other restructuration processes, in 2015 the UN General Assembly resolved to adopt the Basic Principles on Sovereign Debt Restructuring Processes. Among other things, the resolution was a step toward a more equitable system based on contracts and not only economic power. The restructuring processes need to be based on equity principles, in order to avoid what happened to countries like Argentina in the past.

Following the sanction of an anti-vulture law for sovereign debt restructuring processes in Belgium, the European Parliament has called for a review of their legal frameworks in this area. There is a lot of room for improvement in preventing bondholders from taking advantage of developing countries’ weak financial situations. The gaps of the international framework are being discussed in institutions like the IMF. A more equitable framework favors transparency, clear rules and collective action clauses. These types of clauses set a limit to the power a minority of holdouts can have in leveraging a restructuring debt negotiation by forcing them to accept the conditions that the majority agrees on.

Many countries of Latin America and other regions of the developing world are being forced to adopt exceptional financial measures in order to respond to the pandemic. This has a direct effect both on the governments’ economic policies and society. Last November, a group of activists burned the Congress of Guatemala protesting against a major increment of the public debt and significant cuts of the education, health, and welfare budget. The developing world’s current financial situation shows how important it is for the international community to cooperate to address severe social inequality gaps.